EL

MARAVILLOSO

EGIPTO

Cambises II

Creado por juancas del 10 de Octubre del 2012

1995EA - Cambises-II

for everyone

Cambises II

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

| Cambises II | |

|---|---|

| Gran Rey y Faraón de Egipto | |

Miniatura 12 de la Sinopsis histórica de Constantino Manasés, siglo XIV: reyes Cambises, Giges y Darío, escaneado del libro "Miniaturas de la Crónica de Manasés", Ivan Duichev, "Bulgarski hudojnik" Publishing house, Sofía, 1962 | |

| Reinado | 528-521 a. C. (como rey de Persia) y desde 525 a. C., faraón de Egipto |

| Fallecimiento | 521 a. C. |

| Predecesor | Ciro el Grande (Persia) Psamético III (Egipto) |

| Sucesor | Esmerdis (Persia y Egipto) |

| Dinastía | Aqueménida |

| Padre | Ciro el Grande |

Cambises II (en persa کمبوجیه Kambujiya) (muerto en 521 a. C.), rey de Persia de la dinastía aqueménida (528-521 a. C.), hijo y heredero de Ciro II el Grande, fundador del Imperio persa aqueménida.

Ascenso al trono [editar]

Cuando Ciro II conquistó Babilonia en el año 539 a. C., Cambises fue el encargado de dirigir las ceremonias religiosas (según cuenta la Crónica de Nabónido), y en el cilindro que contiene la proclamación de Ciro a los babilonios, el nombre de Cambises está ligado al de su padre en las oraciones a Marduk. En una tablilla fechada en el primer año del reinado de Ciro, Cambises es mencionado como rey de Babel; sin embargo su autoridad debió ser efímera, pues hasta el año 530 a. C. Cambises no fue asociado al trono, cuando Ciro partió hacia su última campaña contra los masagetas del Asia Central. Se han hallado numerosas tablillas en Babilonia de este momento de su ascensión y de su primer año de reinado, y donde Ciro es denominado "rey de naciones" (sinónimo de "rey del mundo").

Tras el fallecimiento de su padre en la estación de la primavera del 528 a. C., Cambises se convirtió en el soberano único del Imperio persa. Las tablillas encontradas en Babilonia acerca de su reinado abarcan hasta su octavo año de reinado, concretamente hasta marzo del 521 a. C. Heródoto (3. 66) establece su reinado desde la muerte de Ciro, y le otorga una duración de siete años y cinco meses, desde el año 528 a. C. hasta el verano del 521 a. C.

Campañas africanas [editar]

Era bastante normal que, tras la conquista de los países asiáticos por parte de Ciro, Cambises decidiera emprender la conquista de Egipto, el único estado independiente que subsistía en Oriente. Antes de partir con su expedición, mandó asesinar a su hermano Esmerdis, el cual había sido designado por Ciro como gobernador de las provincias orientales del Imperio. Esta información es proporcionada por Darío I en la inscripción de Behistún, mientras que los autores griegos clásicos indican que su asesinato se produjo tras la conquista de Egipto.

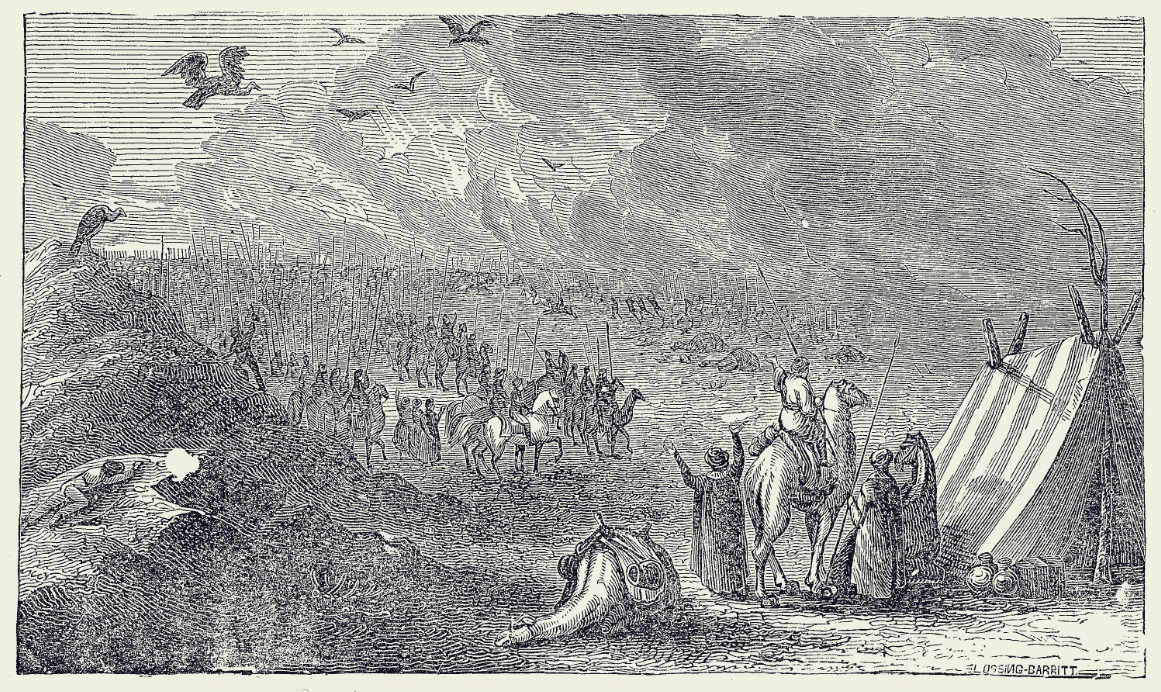

La guerra comenzó en el 525 a. C., cuando el faraón Ahmose II fue sucedido por su hijo Psamético III. Cambises había preparado la marcha de su ejército a través del desierto del Sinaí con la ayuda de tribus árabes, que le prepararon depósitos de agua, esenciales para cruzar el desierto. La esperanza del anterior faraón egipcio, Ahmose II, para conjurar la amenaza persa se basaba en una alianza con los griegos. Sin embargo, su esperanza fue vana cuando comprobó que las ciudades chipriotas y el tirano Polícrates de Samos (quien poseía una poderosa flota) decidieron pasarse al bando persa, como también hiciera Fanes de Halicarnaso, comandante de las tropas griegas mercenarias en Egipto, y el egipcio Udjahorresne de Sais, jefe de la flota egipcia.

Finalmente, en la decisiva batalla de Pelusio, los egipcios fueron derrotados por los persas, y poco después Menfis caía en manos de Cambises. Psamético fue capturado, y posteriormente ejecutado tras intentar una rebelión. Las inscripciones egipcias de este periodo muestran que Cambises adoptó oficialmente los títulos y costumbres de los faraones, si bien es factible creer que no ocultó su desprecio por las costumbres y la religión egipcia.

Desde Egipto, Cambises planificó la conquista de los reinos nubios de Napata y Meroe, ubicados en el actual Sudán, pero su ejército fue incapaz de atravesar el desierto nubio, sufriendo elevadas pérdidas que le obligaron a retirarse. En una inscripción hallada en Napata, actualmente ubicada en el Museo de Berlín, el rey nubio Nastesen describe su victoria sobre las tropas de Kembasuden y la captura de sus barcos, personaje que se identifica con Cambises.(1) De la misma forma, otra expedición de Cambises al oasis de Siwa también fracasó, además de tener que renunciar a su proyecto de conquistar Cartago debido a la negativa de sus marineros fenicios a atacar a sus compatriotas, siendo la flota de sus súbditos fenicios esencial para cruzar el Mar Mediterráneo y salvar así el desierto libio.

El final de Cambises [editar]

Mientras Cambises llevaba a cabo estas tentativas de expansión por África, en Persia un mago llamado Gaumata se hizo pasar por el hermano de Cambises, Esmerdis, que el rey había ordenado matar previamente y en secreto, ante el temor de que se rebelase contra él tras partir hacia Egipto. De esta forma Gaumata consiguió el apoyo del pueblo, tras dictar varias medidas favorables, por lo que Cambises decidió emprender el retorno a Persia y castigar al usurpador. Sin embargo, comprobando finalmente que no podría vencer la revuelta, acabó suicidándose en marzo del 521 a. C., tal como narra Darío I en la inscripción de Behistún, mientras que Heródoto y Ctesias afirman, con menor credibilidad, que su muerte se debió a un accidente. Heródoto narra que Cambises murió en Ecbatana de Siria, la actual Hama (3.64); Flavio Josefo señala que su muerte se produjo en Damasco (Antigüedades, xi. 2. 2); mientras que Ctesias aboga por la ciudad de Babilonia, algo difícilmente posible. (2)

Tradiciones acerca de Cambises [editar]

Hay varias fuentes principales que proporcionan la información existente acerca del reinado de Cambises, entre las que destacan las de los autores griegos Heródoto y Ctesias. El primero nos habla de Cambises en su relato de la historia de Egipto (3. 2-4; 10-37), donde Cambises aparece como el hijo legítimo de Ciro y de Nitetis, hija del faraón Apries. La muerte de Apries a manos del usurpador Ahmose II fue el hecho que decidió a Cambises a vengarse del usurpador.

Esta versión de la historia es corregida por las tradiciones persas que también recoge Ctesias (Athen. Xiii. 560) y también Heródoto, y que explican que Cambises deseaba contraer matrimonio con una de las hijas de Ahmose, pero el faraón egipcio, consciente de que sólo las mujeres persas eran declaradas reinas consortes, comprendió que su hija acabaría formando parte del harén real persa. De esta forma decidió enviar a Cambises a una hija de su predecesor Apries, quien, humillado al descubrir este engaño, decidió vengarse preparando la invasión de Egipto.

Ahmose ya había muerto para cuando Cambises conquistó el país, por lo que su venganza recayó en su hijo Psamético III, al que hizo beber la sangre del dios-toro Apis, por lo cual fue castigado con la locura, según las fuentes clásicas. De esta forma, Cambises en su locura acabó con la vida de su hermano y su hermana Roxana, perdiendo finalmente su imperio a manos de un usurpador y muriendo a causa de una herida (quizás autoinducida) en la cadera, el mismo lugar donde había mandado herir al animal sagrado. Otra historia relacionada con Cambises es la de Fanes de Halicarnaso, el jefe de los mercenarios griegos al servicio del faraón Ahmose II, que decidió buscar la protección del rey persa, y que pagó su traición con la cruel muerte de sus dos hijos, que permanecieron en Egipto.

La tradición persa, por el contrario, cuenta que la causa de su locura fue el asesinato de su hermano Esmerdis, lo cual, unido a los abusos de la bebida, fueron señalados como causas de su prematura ruina.

Todas estas tradiciones se basan en diferentes pasajes tardíos de Heródoto, complementados con detalles familiares poco fiables de los fragmentos de Ctesias. Con la excepción de la escasa información que proporcionan las tablillas babilonias y algunas inscripciones egipcias, la única fuente de información coetánea que poseemos del reinado de Cambises es el relato de Darío I en la inscripción de Behistún. Es por ello que es difícil tener una imagen correcta acerca del carácter real Cambises, si bien todo apunta ciertamente a que se trató de un soberano déspota y sanguinario.

El ejército perdido de Cambises [editar]

De acuerdo con Heródoto, Cambises envió un ejército de 50.000 hombres para someter al oráculo de Amón, ubicado en el oasis de Siwa. Cuando ya había atravesado la mitad del desierto que separa el oasis del valle del Nilo, una tormenta de arena se abatió sobre el ejército, sepultándolo para siempre. Muchos egiptólogos consideran esta historia como una leyenda, si bien mucha gente ha tratado de encontrar los restos de este ejército durante mucho tiempo. Entre ellos se cuentan el conde László Almásy (en el que se basa la novela El paciente inglés, de Michael Ondaatje) y el moderno geólogo Tom Brown. Hay quienes piensan que en algunas excavaciones petrolíferas recientes se han hallado evidencias que demuestan la existencia de este ejército. La novela de Paul Sussman El enigma de Cambises narra la historia de las expediciones arqueológicas que rivalizaron en busca de sus restos.(3) En noviembre de 2009, un equipo de arqueólogos italianos asegura haber encontrados muchos restos de soldados sepultados bajos las arenas del desierto del Sáhara, al sur de Siwa; los arqueólogos Angelo y Alfredo Castiglioni hallaron artefactos aqueménidas que datan de la época de Cambises: armas de bronce, un brazalete de plata, pendientes y cientos de huesos humanos.[1]

Titulatura [editar]

| Titulatura | Jeroglífico | Transliteración (transcripción) - traducción - (procedencia) |

| Nombre de Horus: |

| sm3 ta.uy (Sematauy) El que unifica las Dos Tierras (Egipto) |

| Nombre de Nesut-Bity: |

| ms ti rˁ (Anjkara) Heredero de Ra |

| Nombre de Sa-Ra: |

| k m b i ṯ t (kembechet) Cambises |

Véase también [editar]

Referencias [editar]

Notas bibliográficas [editar]

1.- Schafer, H. (1901): Die Aethiopische Königsinschrift des Berliner Museums

2.- Lincke, A (1897): "Kambyses in der Sage, Litteratur und Kunst des Mittelalters", en Aegyptiaca: Festschrift für Georg Ebers, Leipzig, pp. 41-61.

3.- Sussman, P. (2004) El enigma de Cambises. (ISBN 84-9793-231-5)

Enlaces externos [editar]

- Cambises II (en inglés) En www.livius.org

- Cambises II, en digitalegypt. University College London.

- Irán quiere enviar un equipo a estudiar unos restos del ejército de Cambises En www.canalpatrimonio.com

| Predecesor: Ciro II el Grande | Rey de Persia 528–521 a. C. | Sucesor: Esmerdis |

| Predecesor: Psamético III | Faraón de Egipto 525–521 a. C. | Sucesor: Esmerdis |

Categorías: Faraones | Dinastía XXVII | Reyes de la Dinastía Aqueménida | Nacidos en año desconocido | Fallecidos en 522 a. C. | Reyes de Persia

Categories: 522 BC deaths | Monarchs of Persia | Pharaohs of the Achaemenid dynasty of Egypt | Achaemenid kings | 6th-century BC rulers | Characters in Herodotus | Cause of death disputed

Cambyses II

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Cambyses" redirects here. For other uses, see Cambyses (disambiguation).

Cambyses II (Old Persian: 𐎣𐎲𐎢𐎪𐎡𐎹 [1] Kambūjiya[2], Persian: کمبوجیه, d. 522 BC) was the son of Cyrus the Great (r. 559-530 BC), founder of the Persian Empire and its first dynasty. His grandfather was Cambyses I, king of Anshan. Following Cyrus' conquests of the Near East and Central Asia, Cambyses further expanded the empire into Egypt during the Late Period. His forces invaded the Kingdom of Kush (located in what is now the Republic of Sudan) without any breakthrough successes.

[edit] Rise to power

When Cyrus The Great conquered Babylon in 539 BC, he was employed in leading religious ceremonies,[3] and in the cylinder which contains Cyrus' proclamation to the Babylonians his name is joined to that of his father in the prayers to Marduk. On a tablet dated from the first year of Cyrus, Cambyses is called king of Babylon, although his authority seems to have been quite ephemeral; it was only in 530 BC, when Cyrus set out on his last expedition into the East, that he associated Cambyses on the throne, and numerous Babylonian tablets of this time are dated from the accession and the first year of Cambyses, when Cyrus was "king of the countries" (i.e. of the world). After the death of his father in August 530, Cambyses became sole king. The tablets dated from his reign in Babylonia run to the end of his eighth year, i.e. March 522 BC. Herodotus (3.66), who dates his reign from the death of Cyrus, gives him seven years five months, i.e. from 530 BC to the summer of 523.[4]

[edit] The traditions of Cambyses

The traditions about Cambyses, preserved by the Greek authors, come from two different sources. The first, which forms the main part of the account of Herodotus (3. 2-4; 10-37), is of Egyptian origin. Here Cambyses is made the legitimate son of Cyrus and a daughter of Apries named Nitetis (Herod. 3.2, Dinon fr. II, Polyaen. viii. 29), whose death he avenges on the successor of the usurper Amasis. Nevertheless, (Herod. 3.1 and Ctesias a/i. Athen. Xiii. 560), the Persians corrected this tradition:

Cambyses wants to marry a daughter of Amasis, who sends him a daughter of Apries instead of his own daughter, and by her Cambyses is induced to begin the war. His great crime is the killing of the Apis bull, for which he is punished by madness, in which he commits many other crimes, kills his brother and his sister, and at last loses his empire and dies from a wound in the thigh, at the same place where he had wounded the sacred animal. Intermingled are some stories derived from the Greek mercenaries, especially about their leader Phanes of Halicarnassus, who betrayed Egypt to the Persians. In the Persian tradition the crime of Cambyses is the murder of his brother; he is further accused of drunkenness, in which he commits many crimes, and thus accelerates his ruin.

These traditions are found in different passages of Herodotus, and in a later form, but with some trustworthy detail about his household, in the fragments of Ctesias. With the exception of Babylonian dated tablets and some Egyptian inscriptions, we possess no contemporary evidence about the reign of Cambyses but the short account of Darius in the Behistun Inscription. It is impossible from these sources to form a correct picture of Cambyses' character; but it seems certain that he was a wild despot and that he was led by drunkenness to many atrocious deeds.[citation needed]

[edit] Darius' account

[edit] Conquest of Egypt

Further information: Battle of Pelusium (525 BC)

It was quite natural that, after Cyrus had conquered the Middle East, Cambyses should undertake the conquest of Egypt, the only remaining independent state in that part of the world. The war took place in 525 BC, when Amasis II had just been succeeded by his son Psamtik III. Cambyses had prepared for the march through the desert by an alliance with Arabian chieftains, who brought a large supply of water to the stations. King Amasis had hoped that Egypt would be able to withstand the threatened Persian attack by an alliance with the Greeks.

But this hope failed, as the Cypriot towns and the tyrant Polycrates of Samos, who possessed a large fleet, now preferred to join the Persians, and the commander of the Greek troops, Phanes of Halicarnassus, went over to them. In the decisive battle at Pelusium the Egyptian army was defeated, and shortly afterwards Memphis was taken. The captive king Psammetichus was executed, having attempted a rebellion. The Egyptian inscriptions show that Cambyses officially adopted the titles and the costume of the Pharaohs.

[edit] Attempts to conquer south and west of Egypt

From Egypt, Cambyses attempted the conquest of Kush, located in the modern Sudan. But his army was not able to cross the deserts and after heavy losses he was forced to return. In an inscription from Napata (in the Berlin museum) the Nubian king Nastasen relates that he had defeated the troops of "Kambasuten" and taken all his ships. This was once thought to refer to Cambyses II (H. Schafer, Die Aethiopische Königsinschrift des Berliner Museums, 1901); however, Nastasen lived far later and was likely referring to Khabash. Another expedition against the Siwa Oasis failed likewise, and the plan of attacking Carthage was frustrated by the refusal of the Phoenicians to operate against their kindred.

[edit] The death of Cambyses

According to most ancient historians, in Persia the throne was seized by a man posing as his brother Bardiya, who had really been killed by Cambyses a few years earlier. Some modern historians consider that this person really was Bardiya, the story that he was an impostor was created by Darius after he became monarch.

Whoever this new monarch may have been, Cambyses attempted to march against him, but died shortly after under disputed circumstances. According to Darius, who was Cambyses' lance-bearer at the time, he decided that success was impossible, and died by his own hand in March 522 BCE. Herodotus and Ctesias ascribe his death to an accident. Their story is that while mounting his horse, the tip of his scabbard broke and his sword pierced his thigh - Herodotus mentions it is the same place where he stabbed a sacred cow in Egypt. He then died of gangrene of the bone and mortification of the wound. Some modern historians suspect that Cambyses may have been assassinated, either by Darius as the first step to usurping the empire for himself, or by supporters of Bardiya.[5][6] According to Herodotus (3.64) he died in Ecbatana, i.e. Hamath; Josephus (Antiquites xi. 2. 2) names Damascus; Ctesias, Babylon, which is absolutely impossible.[7]

Cambyses was buried in Pasargadae. The remains of his tomb were identified in 2006.[8]

[edit] The Lost Army of Cambyses

According to Herodotus 3.26, Cambyses sent an army to threaten the Oracle of Amun at the Siwa Oasis. The army of 50,000 men was halfway across the desert when a massive sandstorm sprang up, burying them all. Although many Egyptologists regard the story as a myth, people have searched for the remains of the soldiers for many years. These have included Count László Almásy (on whom the novel The English Patient was based) and modern geologist Tom Brown. Some believe that in recent petroleum excavations, the remains may have been uncovered.[9]

In January 1933, Orde Wingate--later famous for creating the Chindits, allied troops that fought behind enemy lines against the Japanese during World War II--searched unsuccessfully for the Lost Army of Cambyses in the Egypt's Western Desert, then known as the Libyan Desert.

On February 17, 1977, Associated Press reporter Marcus K. Smith wrote the following story, whose headline read: "Lost Army Found."

CAIRO—The remains of an invading Persian army that vanished in a sandstorm 2,500 years ago have been uncovered in the Egyptian Western Desert. An Egyptian archaeological mission discovered thousands of bones, swords, and spears of Persian manufacture of the vanished army of King Cambyses at the foot of Abu Balas Mountain. The site is in a region twice the size of Switzerland, known as the 'Great Sea of Sand.' Archaeologists are calling it one of the greatest finds of the century. The site is not far from the Siwa (Amon) Oasis, 350 miles west of Cairo which the Persian soldiers were trying to reach when they were overwhelmed by a desert storm...

This story proved to be a hoax.

From September 1983 to February 1984, Gary S. Chafetz, an American journalist and author, led an expedition--sponsored by Harvard University, The National Geographic Society, the Egyptian Geological Survey and Mining Authority, and the Ligabue Research Institute--that searched for the Lost Army of Cambyses. The six-month search was conducted along the Egyptian-Libyan border in a remote 100-square-kilometer area of complex dunes south west of the uninhabited Bahrein Oasis, approximately 100 miles south east of Siwa (Amon) Oasis. The $250,000 expedition had at its disposal 20 Egyptian geologists and laborers, a National Geographic photographer, two Harvard Film Studies documentary filmmakers, three camels, an ultra-light aircraft, and ground-penetrating radar. The expedition discovered approximately 500 tumili (Zoroastrian-style graves) but no artifacts. Several tumili contained bone fragments. Thermoluminence later dated these fragments to 1,500 B.C., approximately 1000 years earlier than the Lost Army. A recumbent winged sphinx carved in oolitic limestone was also discovered in a cave in the uninhabited Sitra Oasis (between Bahrein and Siwa Oases), whose provenance appeared to be Persian. Chafetz was arrested when he returned to Cairo in February 1984 for "smuggling an airplane into Egypt," even though he had the written permission of the Egyptian Geological Survey and Mining Authority to bring the aircraft into the country. He was interrogated for 24 hours. The charges were dropped after he promised to donate the ultra-light to the Egyptian Government. The aircraft now sits in the Egyptian War Museum in Cairo with a plaque that reads: "Captured from an Israeli Spy."[10][11][12]http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1347&dat=19831007&id=Sh0VAAAAIBAJ&sjid=rPsDAAAAIBAJ&pg=5624,2799052

In the summer of 2000, a Helwan University geological team, prospecting for petroleum in Egypt's Western Desert, came across well-preserved fragments of textiles, bits of metal resembling weapons, and human remains that they believed to be traces of the Lost Army of Cambyses. The Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities announced that it would organize an expedition to investigate the site, but released no further information.[13]

In November 2009, two Italian archaeologists, Angelo and Alfredo Castiglioni, announced the discovery of human remains, tools and weapons which date to the era of the Persian army. These artifacts were located near Siwa Oasis.[14] According to these two archaeologists this is the first archaeological evidence of the story reported by Herodotus. While working in the area, the researchers noticed a half-buried pot and some human remains. Then the brothers spotted something really intriguing -- what could have been a natural shelter. It was a rock about 35 meters (114.8 feet) long, 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) in height and 3 meters (9.8 feet) deep. Such natural formations occur in the desert, but this large rock was the only one in a large area.[15]

However, these “two Italian archaelogists" presented their discoveries in a film rather than a scientific journal. Doubts have been raised because the Castiglioni brothers also happen to be the two filmmakers who produced five controversial African shockumentaries in the 1970s--including Addio ultimo uomo, Africa ama, and Africa dolce e selvaggia--films in which audiences saw unedited footage of the severing of a penis, the skinning of a human corpse, the deflowering of a girl with a stone phallus, and a group of hunters tearing apart an elephant’s carcass.[16]

The Secretary General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, Zahi Hawass, has said in a press release that media reports of this "are unfounded and misleading" and that "The Castiglioni brothers have not been granted permission by the SCA to excavate in Egypt, so anything they claim to find is not to be believed."[17]

[edit] Fictional representations of Cambyses

- Thomas Preston's play King Cambyses, a lamentable Tragedy, mixed full of pleasant mirth was probably produced in the 1560s.

- A tragedy by Elkanah Settle, Cambyses, King of Persia, was produced in 1667.

- Cambyses and his downfall are also central to egyptologist Georg Ebers' 1864 novel, Eine ägyptische Königstochter ("An Egyptian Princess").

- Cambyses' lost army appears in Biggles Flies South

- Robert E. Howard wrote a poem, "Skulls and Dust", about Cambyses' death.

- A 2002 novel by Paul Sussman The Lost Army of Cambyses (ISBN 0-593-04876-8) recounts the story of rival archaeological expeditions searching for the remains.

[edit] Notes

- ^ Akbarzadeh, D.; A. Yahyanezhad (2006) (in Persian). The Behistun Inscriptions (Old Persian Texts). Khaneye-Farhikhtagan-e Honarhaye Sonati. p. 59. ISBN 964-8499-05-5.

- ^ Kent, Ronald Grubb (1384 AP) (in Persian). Old Persian: Grammar, Text, Glossary. translated into Persian by S. Oryan. pp. 395. ISBN 964-421-045-X.

- ^ Nabonidus Chronicle

- ^ For the dates, see Parker & Dubberstein, Babylonian Chronology.

- ^ http://www.herodotuswebsite.co.uk/darius.htm

- ^ Van Der Mieroop A History of the Ancient Near East

- ^ See A. Lincke, "Kambyses in der Sage, Litteratur und Kunst des Mittelalters", in Aegyptiaca: Festschrift für Georg Ebers (Leipzig 1897), pp. 41-61; also History of Persia.

- ^ "Discovered Stone Slab Proved to be Gate of Cambyses’ Tomb by Cultural Heritage New Agency.

- ^ Cambyses' Lost Army

- ^ http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1347&dat=19831007&id=Sh0VAAAAIBAJ&sjid=rPsDAAAAIBAJ&pg=5624,2799052

- ^ http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1367&dat=19840209&id=GZwWAAAAIBAJ&sjid=kBMEAAAAIBAJ&pg=3613,2156479

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=qUk0GyDJRCoC&pg=PA678&lpg=PA678&dq=lost+army+of+cambyses+%2B+chafetz&source=bl&ots=ObAXx4CgGs&sig=dlTKeZU3FjsWCos9SXOb6V1BLbo&hl=en&ei=qgb_SqvhCInVlQe4leXeDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CCAQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=lost%20army%20of%20cambyses%20%2B%20chafetz&f=false

- ^ http://www.archaeology.org/0009/newsbriefs/cambyses.html

- ^ Lorenzi, Rossella (2009-11-09). "Vanished Persian army said found in desert". MSNBC.com. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/33791672/ns/technology_and_science-science. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- ^ {cite news |url=http://news.discovery.com/archaeology/the-quest-for-cambyses-lost-army.html |title=The Quest for Cambyses' Last Army | |first=Rossella |last=Lorenzi |publisher=discovery.com |date=2009-11-09 |accessdate=2009-11-22}}

- ^ http://www.pulpinternational.com/pulp/section/Mondo%20Bizarro.html

- ^ Hawass, Zahi "Press Release- Alleged Finds in Western Desert " [1]

[edit] Literature

- Ebers, Georg. An Egyptian Princess 1864. (English translation of Eine ägyptische Königstochter) at Project Gutenberg.

- Preston, Thomas. Cambises 1667. Plaintext ed. Gerard NeCastro (closer to original spelling) in his collection Medieval and Renaissance Drama.

- Cambyses by Ahmed Shawqi

[edit] External links

Cambyses II

Born: ?? Died: 521 | ||

| Preceded by Cyrus the Great | Great King (Shah) of Persia 530–522 | Succeeded by Bardiya |

| Preceded by Psammetichus III | Pharaoh of Egypt 525–522 | |

Categories: 522 BC deaths | Monarchs of Persia | Pharaohs of the Achaemenid dynasty of Egypt | Achaemenid kings | 6th-century BC rulers | Characters in Herodotus | Cause of death disputed

En otros idiomas

- Afrikaans

- العربية

- Беларуская (тарашкевіца)

- Български

- Català

- Česky

- Cymraeg

- Deutsch

- English

- Esperanto

- Eesti

- فارسی

- Suomi

- Français

- Galego

- עברית

- Hrvatski

- Magyar

- Italiano

- 日本語

- 한국어

- Nederlands

- Norsk (bokmål)

- Polski

- Português

- Русский

- Srpskohrvatski / Српскохрватски

- Slovenčina

- Slovenščina

- Српски / Srpski

- Svenska

- Türkçe

- Tiếng Việt

- ייִדיש

- 中文

AUDIOS IVOOX.COM y EMBEDR PLAYLIST

IVOOX.COM

PRINCIPALES de ivoox.com

- BIBLIA - LINKS en ivoox.com - domingo, 26 de agosto de 2012

- BIOGRAFÍAS - LINKS - ivoox.com - domingo, 26 de agosto de 2012

- EGIPTO - LINKS - ivoox.com - domingo, 26 de agosto de 2012

- Deepak Chopra - Eckchart Tolle - LINKS - ivoox.com - martes, 28 de agosto de 2012

- HISTORIA en GENERAL - LINKS - jueves, 4 de octubre de 2012

BIBLIA I - LINKS en ivoox.com

BIOGRAFÍAS - LINKS - ivoox.com

EGIPTO - LINKS - ivoox.com

Deepak Chopra - Eckchart Tolle - LINKS - ivoox.com

HISTORIA en GENERAL - LINKS

PLAYLIST - EMBEDR

- JESUCRITO I - viernes 13 de enero de 2012

- Mundo Religioso 1 - miércoles 28 de diciembre de 2011

- Mundo Religioso 2 - jueves 29 de diciembre de 2011

- Mitología Universal 1 (Asturiana) - jueves 29 de diciembre de 2011

- El Narrador de Cuentos - UNO - jueves 29 de diciembre de 2011

- El Narrador de Cuentos - DOS - jueves 29 de diciembre de 2011

MEDICINA NATURAL, RELAJACION

- Medicina Natural - Las Plantas Medicinales 1 (Teoría) - miércoles 28 de diciembre de 2011

- Medicina Natural - Plantas Medicinales 1 y 2 (Visión de las Plantas) - miércoles 28 de diciembre de 2011

- Practica de MEDITATION & RELAXATION 1 - viernes 6 de enero de 2012

- Practica de MEDITATION & RELAXATION 2 - sábado 7 de enero de 2012

VAISHNAVAS, HINDUISMO

- KRSNA - RAMA - VISHNU - jueves 16 de febrero de 2012

- Gopal Krishna Movies - jueves 16 de febrero de 2012

- Yamuna Devi Dasi - jueves 16 de febrero de 2012

- SRILA PRABHUPADA I - miércoles 15 de febrero de 2012

- SRILA PRABHUPADA II - miércoles 15 de febrero de 2012

- KUMBHA MELA - miércoles 15 de febrero de 2012

- AVANTIKA DEVI DASI - NÉCTAR BHAJANS - miércoles 15 de febrero de 2012

- GANGA DEVI MATA - miércoles 15 de febrero de 2012

- SLOKAS y MANTRAS I - lunes 13 de febrero de 2012

- GAYATRI & SHANTI MANTRAS - martes 14 de febrero de 2012

- Lugares Sagrados de la India 1 - miércoles 28 de diciembre de 2011

- Devoción - PLAYLIST - jueves 29 de diciembre de 2011

- La Sabiduria de los Maestros 1 - jueves 29 de diciembre de 2011

- La Sabiduria de los Maestros 2 - jueves 29 de diciembre de 2011

- La Sabiduria de los Maestros 3 - jueves 29 de diciembre de 2011

- La Sabiduria de los Maestros 4 - jueves 29 de diciembre de 2011

- La Sabiduría de los Maestros 5 - jueves 29 de diciembre de 2011

- Universalidad 1 - miércoles 4 de enero de 2012

Biografías

- Biografía de los Clasicos Antiguos Latinos 1 - viernes 30 de diciembre de 2011

- Swami Premananda - PLAYLIST - jueves 29 de diciembre de 2011

Romanos

- Emperadores Romanos I - domingo 1 de enero de 2012

Egipto

- Ajenaton, momias doradas, Hatshepsut, Cleopatra - sábado 31 de diciembre de 2011

- EL MARAVILLOSO EGIPTO I - jueves 12 de enero de 2012

- EL MARAVILLOSO EGIPTO II - sábado 14 de enero de 2012

- EL MARAVILLOSO EGIPTO III - lunes 16 de enero de 2012

- EL MARAVILLOSO EGIPTO IV - martes 17 de enero de 2012

- EL MARAVILLOSO EGIPTO V - miércoles 18 de enero de 2012

- EL MARAVILLOSO EGIPTO VI - sábado 21 de enero de 2012

- EL MARAVILLOSO EGIPTO VII - martes 24 de enero de 2012

- EL MARAVILLOSO EGIPTO VIII - viernes 27 de enero de 2012

La Bíblia

- El Mundo Bíblico 1 - lunes 2 de enero de 2012 (de danizia)

- El Mundo Bíblico 2 - martes 3 de enero de 2012 (de danizia)

- El Mundo Bíblico 3 - sábado 14 de enero de 2012

- El Mundo Bíblico 4 - sábado 14 de enero de 2012

- El Mundo Bíblico 5 - martes 21 de febrero de 2012

- El Mundo Bíblico 6 - miércoles 22 de febrero de 2012

- La Bíblia I - lunes 20 de febrero de 2012

- La Bíblia II - martes 10 de enero de 2012

- La Biblia III - martes 10 de enero de 2012

- La Biblia IV - miércoles 11 de enero de 2012

- La Biblia V - sábado 31 de diciembre de 2011

TABLA - FUENTES - FONTS

SOUV2

- SOUV2P.TTF - 57 KB

- SOUV2I.TTF - 59 KB

- SOUV2B.TTF - 56 KB

- SOUV2T.TTF - 56 KB

- bai_____.ttf - 46 KB

- babi____.ttf - 47 KB

- bab_____.ttf - 45 KB

- balaram_.ttf - 45 KB

- SCAGRG__.TTF - 73 KB

- SCAGI__.TTF - 71 KB

- SCAGB__.TTF - 68 KB

- inbenr11.ttf - 64 KB

- inbeno11.ttf - 12 KB

- inbeni11.ttf - 12 KB

- inbenb11.ttf - 66 KB

- indevr20.ttf - 53 KB

- Greek font: BibliaLS Normal

- Greek font: BibliaLS Bold

- Greek font: BibliaLS Bold Italic

- Greek font: BibliaLS Italic

- Hebrew font: Ezra SIL

- Hebrew font: Ezra SIL SR

Disculpen las Molestias

EGIPTOLOGÍA

TABLA de Greek Mythology

Category: Greek Mythology | A - Amp | Amp - Az | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q- R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

Greek Mythology stub | Ab - Al | Ale - Ant | Ant - Az | B | C | D | E | F - G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q - R | R | S | T | A - K | L - Z | Category:Greek deity stubs (593)EA2 | A | B | C | D | E | G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | S | T | U | Z

TABLA de Mitología Romana

TABLA de Otras Ramas de Mitología

Mitología en General 1 | Mitología en General 2 | Category:Festivals in Ancient Greece (2865)JC | Category:Indo-European mythology | Category:Festivals in Ancient Greece (1483)JC | Category:Ancient Olympic Games (1484)JC | Category:Ancient Olympic Games (2876)JC | Category:Ancient Olympic competitors (2889)JC | Category:Ancient Olympic competitors (1485)JC | Category:Ancient Olympic competitors (2910)JC | Category:Ancient Greek athletes (2938)JC | Category:Ancient Greek athletes (1486)JC | Mitología General (3033)SC | 101SC | 3132SC | 3048SC | 3060SC | 3118SC | 3095SC | 876SC | 938SC | 986SC | 1289SC | 1109SC | 1407SC | 1107SC | 2494JC | 2495JC | 2876JC | 2865JC | 2889JC | 2938JC | 2596JC | 2606JC | 2621JC | 2450JC | 1476JC | 1477JC | 2825JC | 2740JC | 2694JC | 2806JC | 2738JC | 2660JC | 2808JC | 2734JC | 2703JC | 2910JC | 3051SK

TABLA - Religión Católica

- Religión Católica

- PAPAS - POPES

- MITOS DE LA BIBLIA

- Via Crucis desde Roma - 10/04/2009 (Completo) (www.populartv.net Oficiado por su Santidad el Papa Benedicto XVI). Papa Juan Pablo II (Karol Wojtyla). (Rosarium Mysteria Gloriosa | Rosarium Mysteria Doloris

- Rosarium Mysteria Gaudii)

- CATHOLIC RELIGION (2020)SK

- Category:Roman Catholicism (3219)SK

- Catolicismo (3220)SK

- Pope o Papas (3243)SK 3. Handel: Brockes Passion, HWV 48 / Marcus Creed (OedipusColoneus) (3243)SK http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QkBV6tEmYx8 4. Handel: Brockes Passion, HWV 48 / Marcus Creed (OedipusColoneus) (3243)SK http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xM3Y5CxvKcg

- Category:Popes (3221)SK

- Listado de Papas desde Pedro hasta el presente (738)EA2

- Catholics

- Misa del Santo Padre Benedicto XVI en la Beatificación del Papa Juan Pablo II

- Juan Pablo II, nuevo beato

- Santos Católicos

- Beato Juan Pablo II - Su Peregrinaje y Su Vida - 1978 al 1986

- Catholics

Vaishnavas

- Sri Garga-Samhita

- Oraciones Selectas al Señor Supremo

- Devotees Vaishnavas

- Dandavat pranams - All glories to Srila Prabhupada

- Hari Katha

- SWAMIS

General

- JUDAISMO

- Buddhism

- El Mundo del ANTIGUO EGIPTO II

- El Antiguo Egipto I | Archivo Cervantes | Sivananda Yoga

- Neale Donald Walsch

- ENCICLOPEDIA - INDICE

- DEVOTOS FACEBOOK

- EGIPTO - USUARIOS de FLICKR y PICASAWEB

- Otros Apartados

- Mejoras

- MULTIPLY y OTRAS

- juancastaneira - JC

- sricaitanyadas - SC

- srikrishnadas - SK

- elagua2 - EA2

- elagua - EA

- casaindiasricaitanyamahaprabhu - CA

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario